Living Totems

Following the global food crisis of 2007-2008, there has been an exponential amount of large-scale land acquisition in Africa. Foreign “land grabs” are redrawing the global map of farmland ownership as foreign direct investments continue the legacy of colonization. Western, Chinese, and Middle Eastern companies are leading a 21st century land rush in African farmland Where more than a 100 million acres are under a 99 year-lease.

Through the consistent extraction in labor, capital and land, the global south is consistently compromised to supply European and North American markets. Foreign corporations are vehemently irrigating rural corners of sub-Saharan Africa, displacing local smallholders from their land to secure stable supplies for the rest of the world.

The project operates within this socio-political and economic backdrop. Greenhouse colonies are architectural representations of this unequal exchanges fostered by global capitalism. The project is an investigation of geopolitical conditions, where architecture is utilized as a lens to expose and respond to current labor-power exploitation.

The production system of Kenyan floriculture is a complex web of biological, mechanical and socioeconomic relationships. The former British Colony is one of the biggest suppliers of bouquets to Europe. Heavily monopolized by Dutch corporations, the multi million-dollar cut-flower industry accounts for 35% of all flower sales in the European Union. However, as 90 percent of the farm operations are foreign owned, these flowers represent a capitalist process of neo-colonial exploitation. The sheer scale of mechanized agro-production has shifted the identity of an individual farmer to a ‘factory worker’.

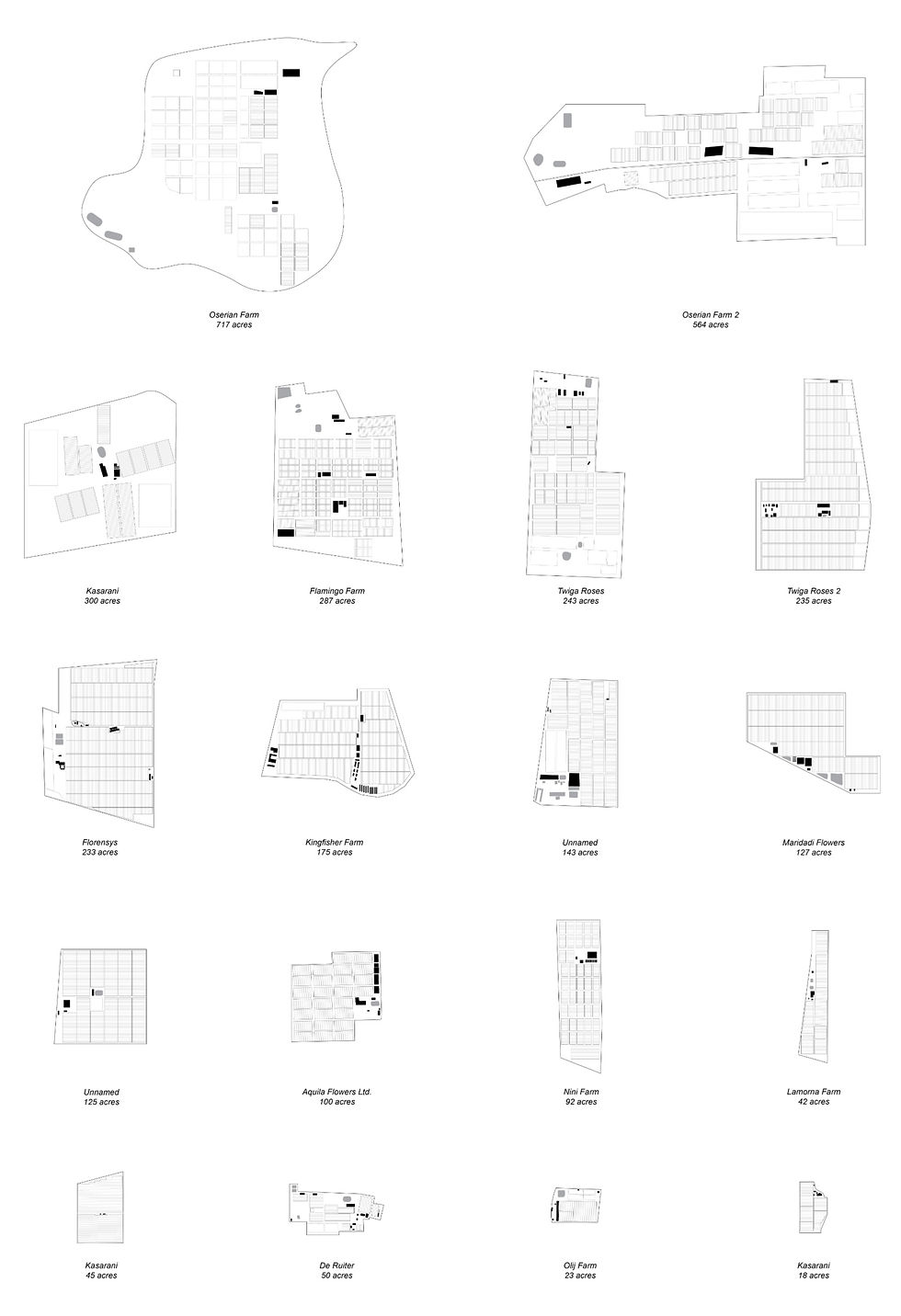

Living Totems is a research-based project on rural development and systems of resiliency. Built in phases of geographical expansion, the smart tech platform connects local farmers to a larger co-operative base. In Phase 1, Architectural icons are sprinkled on a "loose" grid and serves as a physical connection point that decentralizes development. In Phase 2, parasitic prototypes manipulate existing greenhouse structures to provide housing and tourist facilities. At the micro scale, the assembly process in the Agro-factory (breed-grow-cut-pack-waste) is exposed and mediated through digital agricultural devices. At the macro scale, social farming and relational trade is implemented to form a regional Flower Cooperative that rejects the current plantation model. This is a project of utopian realism, and re-imagines labor operations as an architectural spectacle within the reality of global capitalism.

Limitless Platform by Author. www.rosesarered.neocities.org

Agricultural Commons

Industrial systems pose as a non-architectural phenomenon, yet they reflect the seemingly expansive network of a globalized infrastructure that changes our understanding of a rural landscape into a formal one. 21st century Industrial developments in agriculture have irrigated farmland into a controlled “colony” underneath high tunnel structures.

If the popular but misguided “Bilbao Effect” is a resurrection of urban identity through iconic architecture- what is left for the rural? While urban space has been a constant subject of demand in modern discourse, the countryside has been neglected as ‘negative space’ peppered with the occasional fantasy home.

Agro-Industrial hubs such as Almeria, Spain or Westland, Netherlands has seen a geographical take over of climate- controlled farms. As miles and miles of greenhouses extend, an unprecedented scene has formed.

These strange sights offer an opportunity for farmlands to claim a renewed regional identity, to such an extent that a culture of tourism is formed.

On the other hand, horticultural towns such as Hveragerði, Iceland attempt to breed tourism in a sustainable manner. They highlight geothermally powered greenhouses as the future of living, rather than as an unnatural spectacle.

The difference lies in that one is a sighting of neoliberal agrarian development, and the other is based on a localist economy. While they seem to be on the opposite end of farming practices, could there be a better future that meets both halfway? What is the post-capitalist future for industrial agricultural space as a work place?

Following the likes of Joseph Beuys, or Jacques Charlier, I am refusing to conceal the process of production, nor objectify it through means of aesthetisization. Rather, much like Maurizio Cattelan’s 1993 Venice Biennale exhibit “Work Is a Dirty Job”, the project aims to speculate a “precocious proletariat” by turning wage labor into a self-controlled spectacle.

Field Research

Funded by Morris R. Pittman Travel Fellowship (2016, 2017)

Brett Michael Detamore Research Grant (2016)

|

|---|

|

|---|

Geothermal Greenhouse in Iceland (2017) by Author

O'sulloc Tea Museum, Jeju Island (2017) by Author

Site Visit: Lamorna Flower Farm, Kenya (2016) Image by Mina Lee

Site Visit: Lake Naivasha, Kenya (2016) Image by Author

Domestic Assembly

In the wake of Flint, Michigan’s water crisis, the project is an economic intervention for residents to survive when the state fails to provide basic infrastructure such as water, electricity or gas. Mimicking the suburban typology of canopies in strip malls, (such as drive thrus, car washes, atms, gas stations etc.,), housing becomes the framework for an open air structure. The typified Texas Doughnut model is collapsed as the housing aqueduct liberates the ground floor for an explosion of unpredictable programs. The project maintains the overall urban street infrastructure to avoid disrupting the transit system that links the Northside Village to Downtown.

Defined by the highway, the historical wards system of Houston signifies gentrification and segregation of the city. As an infrastructural system, the highway perpetuates suburban sprawl, but as an urban form, the city fails to utilize the unique spatial qualities of its scale. In this missed opportunity, the project seeks alternative ways to extend the public life ‘under’ the highway datum.

Everyone Together Forever

Sharing-economy platforms are no long limited to the likes of airbnb and uber. New online co-living platforms such as Ollie cultivate and design your community through hotel-style micro housing. We live in an era where you design the person who lives across the hall. Collectivity now requires presence in both the online and offline world.

The project addresses both the office space and housing for the “digital nomad” population. Temporality is then reflected in four scales within the project: floor plate, unit, furniture and façade. Difference in floor plates and unit types create a diverse set of spatial connectivity. Operable furniture pieces are designed for individual units and common areas. At the largest scale, a metal scrim façade operates as a kinetic barrier that both encloses and exposes ensuing activities. Spatial design thus activates and blurs the boundaries of privacy.

In Collaboration with Edison Ding.

Recipient of 2017 Margaret Everson Fossi Award

Zilkha Gallery, USA (2011)

video w/ sound

Folding Process, USA (2011)

Memory Activism and Performance Labor

Social memory transgresses reality as its form fades, shifts, and fluctuates over time. The impermanent nature of memory often stands in contrast with the monumental structures of post-war commemoration. In the post-World War II era, war trauma is commodified and permanently reconstructed in urban space in the form of secondhand grieving.

The 30 year-long struggle of Comfort Women Redress Activism in East Asia has often been either ignored or sensationalized by media politics. Geopolitical relations have left the reparation (either monetary or in the form of apology) of forced colonial labor unanswered and undefined. While survivors are burdened by gendered violence during the Pacific War, the politics of memorialism has left them once again laboring in symbolic gestures and media spectacles for the public eye.

This project questions current forms of participation in protest and activism. The Comfort Women Movement has welcomed postwar generations to its grassroots activism. However, memory is a tender thing. The movement often memorializes the living survivors in the fossilized language of violent patriarchy.

During the mark of the 1000th street protests (2011), I documented and interviewed activists across generations. In turn, I adopted the paper folding ritual of East Asia as an act of grieving. Large sheets of paper were transformed through creasing and folding, and the public process became a memorial ritual. The folds create a fluid monumental-scape overlapped with voices of three generations of activists in the ‘comfort women’ movement. I aimed to transform the gallery, a conformative force, into a temporary anti-monument dedicated to ‘comfort women’ and their decades of redress activism. The audience becomes a collaborator in others’ memories by entering, listening and feeling.

In Part of Installation Memory (In)Folds at Zilkha Gallery, USA (2011)